Giant Kelp

Macrocystis pyrifera

Giant Kelp

Macrocystis pyrifera

Low canopy cover of giant kelp in recent years have been so extensive that local recovery has been impacted in some areas.

Morphology

Giant kelp forms magnificent, canopied forests in Southern and Central California. These forests support a complex community of understory seaweeds, invertebrates, and fish. Individuals are anchored to rocky reefs with massive holdfasts, and produce many stem-like stipes that contain fronds bearing golden blades buoyed by oval, gas-filled bladders. These bladders enable the kelp fronds to float near the water surface, maximizing their exposure to sunlight. In some places, individuals can be more than 100 feet long, and fronds can grow over 60 centimeters per day.

Habitat and Range

Giant kelp is considered a “cosmopolitan species” and can be found on temperate coastlines along the west coast of North America, South America in Chile and Peru, and even in South Africa and Australia. On our coast, giant kelp is the dominant canopy-forming species from Central Baja through the Big Sur coast, where it shares dominance with bull kelp. Giant kelp grows from the low intertidal zone to depths of 25 to 30 meters, depending on water clarity and sunlight.

Range Map

Reproductive Biology and Life History

Giant kelp is perennial, living up to 7 years. At maturity, giant kelp forms specialized fronds called sporophylls that grow just above the holdfast. These bear millions of spores that are released in the vicinity of the holdfast. These spores develop into clusters of microscopic filaments that produce either eggs or sperm. After fertilization, the embryo grows into the giant kelp, and the cycle continues. Fronds that have broken away due to wave action or herbivory can tangle into floating rafts that have their own community of fish and invertebrates. It is likely that these can also spread spores, creating new populations. Reefs and kelp can be restored with giant kelp via seeding or outplanting.

Ecology

Giant kelp is an ecological engineer. It is highly efficient at absorbing carbon dioxide and plays a significant role in mitigating climate change. It can absorb more carbon dioxide per acre than most terrestrial forests. Kelp forests also contribute to nutrient cycling by absorbing nutrients such as nitrogen from the water and making them available to other marine organisms. Kelp forests support a diverse community of mammals, fish, invertebrates and other seaweeds by providing three dimensional structure, food, and nutrients. They also dampen or modify wave action. The major consumers of kelp are largely invertebrates, including urchins, abalone, snails and isopods.

Cultural and Historical Context

The economic importance of kelp globally extends to food, medicine, and materials, with historical evidence of its use dating back thousands of years in different cultures around the world. Researchers have suggested that kelp forests along the West Coast of North America, including California, may have facilitated human migration from Asia to the Americas during the late Pleistocene. This theory posits that the rich marine resources provided by these ecosystems supported early coastal communities in need of food. In California, giant kelp supports several iconic species such as red abalone, spiny lobster, and sea otters. California Native American tribes used giant kelp for food directly, as well as utilizing the diversity of species found within giant kelp forests for food and commerce.

Currently, commercial and recreational fishers often focus on kelp forests because of the fish populations they harbor. Recreational divers are also drawn to the beauty of kelp forests, and the aggregations of animals found amidst the kelp. Meanwhile entrepreneurs are exploring the possibility of kelp as a practical biofuel source. In California, kelp farming is slowly gaining traction as a sustainable practice, although it faces challenges with the permitting process. Kelp aquaculture is seen as a way to mitigate climate change impacts, create jobs, and support coastal communities.

Date modified: January 2025

This algae can be found at the Aquarium of the Pacific

Primary ThreatsPrimary Threats Conditions

Threats and Conservation Status

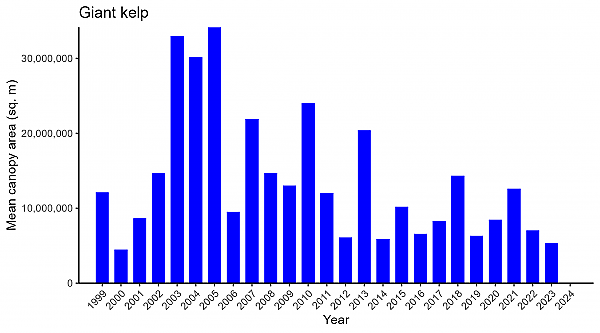

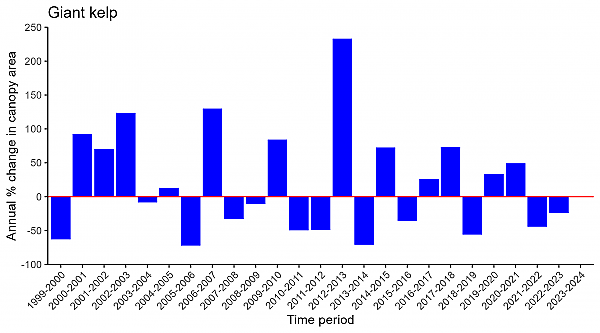

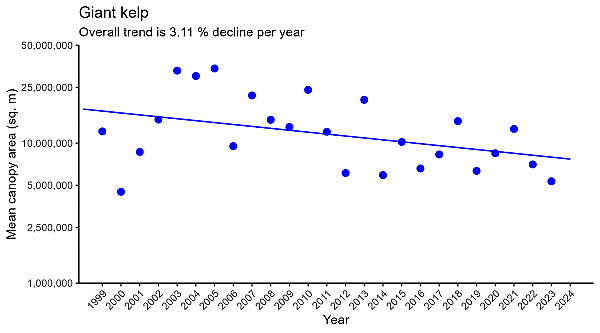

Kelp’s abundance is typically measured in terms of area covered by kelp canopy as detected by aerial surveys and drones. Unfortunately, current satellite-based remote sensing does not allow one to distinguish between giant kelp and bull kelp, but this may be possible in the near future. In the meantime, close observations allow biologists to distinguish the species from field or high-resolution aerial surveys. Giant kelp is the dominant canopy-forming kelp south of the Big Sur coast, but overlaps extensively with bull kelp into the Monterey Bay. Direct observations allow biologists to distinguish the species and from these observations it is known that giant kelp typically occurs south of Point Conception. The data below represents estimates of kelp canopy area south of Point Conception. The mean annual aerial growth rate for kelp in this stretch of coastline is -3% per year, but the population is so variable from year-to-year, that decline explains only 16% of the total year-to-year variation. The population trend is therefore classified as weak decline.

The overall temporal trend for giant kelp is one of alternating “good” (population increase) and “bad” (population decline) years. Giant kelp is in no danger of going extinct, but due to changes in predator-prey relationships, severe storms, and changes in oceanography in certain areas kelp may decline to such an extent that local recovery is impacted.

Human-related threats to kelp forests include pollution, especially sewage run-off, overfishing, sedimentation, and warming water due to climate change. These threats affect kelp forests on multiple temporal and spatial scales. Removal of large, predatory fish, like urchin-eating sheephead, can also disturb the balance of food webs, allowing urchin populations to boom, consume kelp, and form urchin - rather than kelp-dominated habitats. Coastal development can result in increased sediments that decrease water clarity and that may bury or inhibit the microscopic phase of the kelp life cycle. Warmer ocean water does not hold enough nutrients for kelp to thrive and reproduce.

In California, giant kelp has been harvested commercially in the past to produce alginates but that endeavor is currently limited in scale and has shifted to other countries. It is still commercially harvested for aquaculture feed in California, and leases for this are available through the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW).

Population Plots

Data Source: kelpwatch.org