Green Sea Turtle

Chelonia mydas

Green Sea Turtle

Chelonia mydas

An eleven year community science project documents an increasing green sea turtle population in Southern California.

Morphology

Green sea turtles typically grow to 1.5 meters, with an average weight ranging from 68-190 kilograms. The turtle’s body is covered by a large carapace with a streamlined shell design that reduces drag in the water, making them hydrodynamic and efficient swimmers. They have large paddle-like flippers that are used like oars, propelling the turtle through water. They have a rounded head with a short snout and a beak that is specialized for feeding. Lacking teeth, these turtles rely on their serrated beak that can be used like scissors for tearing through tough plant material.

Habitat and Range

Green sea turtles are found in warm subtropical and tropical ocean waters worldwide, with major nesting sites in over 80 countries. They require sandy beaches that provide the right conditions for digging nests and incubating eggs. The sand must be soft enough for the females to dig but firm enough to support the nests. Nesting sites are separated from shallow foraging sites by hundreds of miles, sometimes thousands in the eastern Pacific.

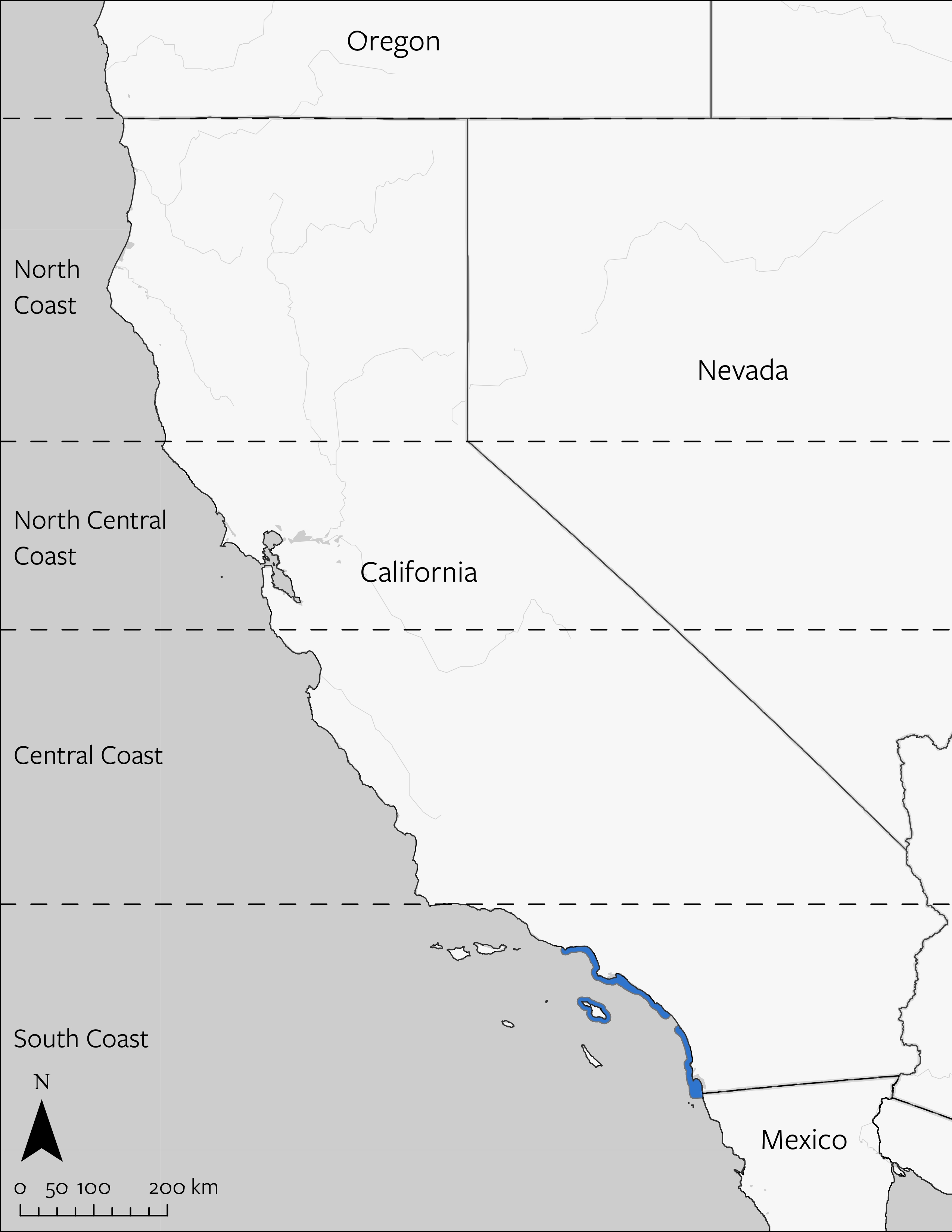

Green sea turtles do not breed or nest in California. Instead, they migrate to California’s coastal waters primarily for foraging. The green sea turtles found in California typically originate from nesting beaches in Mexico. In Southern California, green sea turtles are increasingly seen in bays, lagoons, and estuaries, such as San Diego Bay, the San Gabriel River, Bolsa Chica wetlands, and La Jolla Cove. These areas provide rich feeding grounds with abundant seagrass, algae, and invertebrates. The northernmost population of resident green sea turtles off the Pacific coast of North America occurs near the mouth of the San Gabriel River in Long Beach, California.

Range Map

Reproductive Biology and Life History

Green sea turtles, which in the wild are known to live up to 80 years, do not reach sexual maturity until they are at least twenty years of age. Once mature, both male and female green sea turtles have multiple partners. Mating occurs in shallow waters near nesting beaches, with males using their long claws to grip onto the female’s shell during copulation. On average, females lay five clutches per season, with between 75 and 120 eggs per clutch. The temperature of the sand determines the sex of the hatchlings, with warmer temperatures producing more females. Long distance migrations between nesting sites and shallow foraging areas are common, with females tending to return to their birth sites when they are ready to establish their nests.

Ecology

Green sea turtles are unique among sea turtles due to their herbivorous diet, primarily consisting of seagrasses and algae. This diet contributes to the greenish color of their body fat, which is the origin of their name, rather than the color of their shell. When they are juveniles these turtles are more omnivorous, feeding on sponges, sea urchins, mollusks, and crustaceans. Adult green turtles feed almost exclusively on algae and seagrasses. As large adults their predators are largely limited to sharks, and orcas in some areas. However, as hatchlings and juveniles, green sea turtles have many predators. Eggs on beaches are especially vulnerable to everything from racoons to foxes, birds, crabs, and even ants.

Cultural Significance and Historical Context

Historically, green sea turtles have been exploited by cultures around the world for their fat, skin, meat, and eggs. In the United States, green sea turtles were first listed as endangered in 1978. Since then, their risk status has been downgraded on the U.S. Endangered Species Act to threatened as of 2016. Their nesting sites are now protected around the world, and it is illegal to harvest them in most nations; nevertheless, full recovery has been elusive. Green turtles have played an important role in the cultural history of the Chumash, Tongva, Comcaac and other local coastal communities, where turtle shells are used for ceremonial rattles, and the turtle is associated with the creation of land. In Hawaiian legend, a giant turtle goddess named Kauila could transform into a human girl to protect children playing along the shore.

Date modified: January 2025

This animal can be found at the Aquarium of the Pacific

Primary ThreatsPrimary Threats Conditions

Threats and Conservation Status

The global population of green sea turtles suffered a 90% decline due to human exploitation over the course of 150 years, but during the last 30 years have revered in many areas. Global warming is a concern because temperature has a big impact on turtle sex ratio, with higher temperatures producing a disproportionate number of females, which can reduce hatching success. Ongoing recovery efforts include the careful relocation of sea turtle nests on beaches to protect the eggs from rising beach temperatures, coastal flooding, poaching, and predation.

One of the most pressing threats to sea turtles in Southern California is boat strikes. As boat traffic increases, so does the risk of turtles being struck by boats, which can cause serious injuries or fatalities. Pollution is another threat, especially plastic debris, which can get mistaken for food and ingested by turtles, causing internal injuries, blockages, and even death. High concentrations of heavy metals and organic pollutants have also been found in the blood of green turtles in Southern California. Eelgrass beds, which are vital for foraging, are threatened by coastal development and pollution. These beds provide essential food and habitat for green turtles. Incidental capture, or “bycatch” of green sea turtles in fishing gear, such as nets and longlines, can cause injury or death to them.

Injured turtles are often brought to facilities like the Aquarium of the Pacific for medical treatment and if possible, re-release into nature. The visibility and popularity of green sea turtles makes them an ideal species with which to engage the public in the fate of California marine species in light of human activities and environmental change.

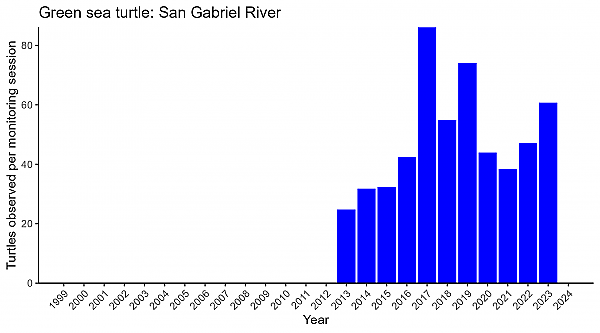

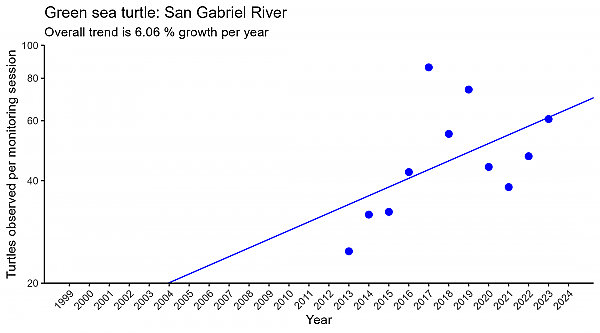

Green sea turtles are one of those iconic marine species the public takes great delight in viewing. Because they are present in Southern California, limited monitoring efforts have been established to track their populations. Here we report data from a community science project that was initiated in 2012 and involves monthly surveys of turtles in the San Gabriel River, using trained volunteers to record data from observation stations along the river. These data show a weak increase population trend.

Population Plots

Data Source: Data comes from the Aquarium of Pacific Community Science turtle monitoring program in the San Gabriel River.